Professional and high-quality metal alloys, ceramic products and concrete additives | RBOSCHCO

In the research of sodium-ion battery (SIBs) cathode materials, P2-type layered oxides have garnered significant attention due to their high specific capacity, low cost, and excellent stability. Among these materials, P2-Naₓ(FeᵧMn₁⁻ʸ)O₂ (iron-manganese-based sodium-ion cathode material) demonstrates outstanding electrochemical performance through the regulation of Fe and Mn ratios. This article delves into the characteristics, synthesis processes, and physical properties of this material, providing valuable insights for the development of sodium-ion batteries.

1. Material Characteristics

1.1 Crystal Structure

P2-Naₓ(FeᵧMn₁⁻ʸ)O₂ belongs to the hexagonal crystal system with space group P6₃/mmc. Its layered structure alternates between [MO₆] octahedral layers and Na⁺ ion layers. The reversible intercalation/deintercalation of Na⁺ ions in the interlayer space endows the material with high specific capacity and rapid charge/discharge capabilities.

1.2 Element Composition and Regulation

Adjusting the Fe/Mn ratio (y value) optimizes electrochemical performance:

- Low y value (Mn-rich): Dominated by Mn³⁺/Mn⁴⁺ redox couples, delivering a high voltage platform (~3.0 V vs. Na⁺/Na) and superior specific capacity.

- High y value (Fe-rich): Additional capacity contribution from Fe³⁺/Fe⁴⁺ redox couples, but may lead to reduced voltage platforms and compromised cycle stability.

1.3 Physical Properties

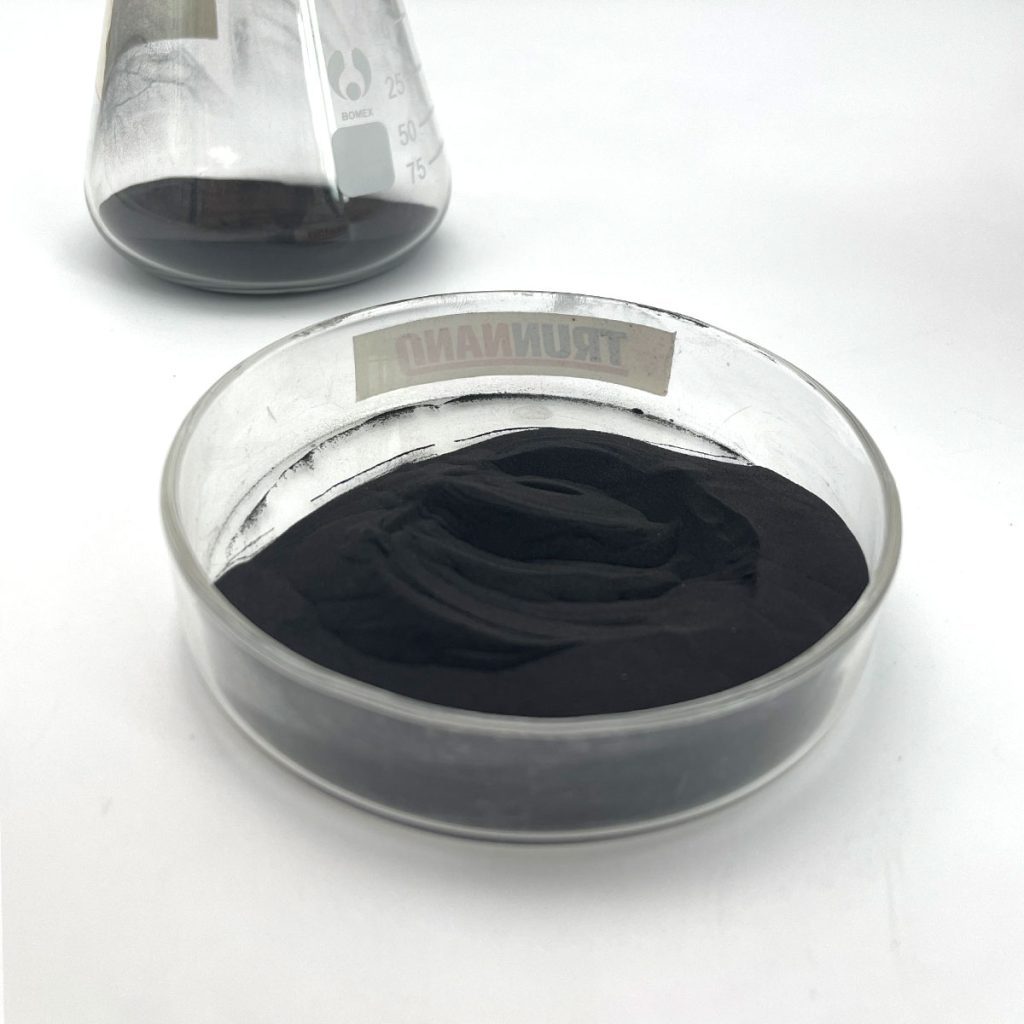

- Color: Deep gray or black, dependent on Fe/Mn ratios.

- Tap Density: Influenced by particle morphology and size, directly affecting electrode compaction density and battery energy density.

- Dry Particle Size (D50): Typically controlled at 5–15 μm; excessively fine particles hinder electrode processing, while oversized particles reduce ion diffusion rates.

- Residual Alkali pH Value: Regulated via washing processes to prevent side reactions and extend cycle life.

2. Electrochemical Performance

2.1 Specific Capacity

- Theoretical Specific Capacity: 120–150 mAh/g. Practical capacities reach 100–130 mAh/g (at 0.1C rate) through optimized y values and synthesis processes.

- Voltage Platform: Mn-rich materials exhibit a stable platform at 2.5–3.0 V, while Fe-rich materials contribute additional capacity at 2.5–2.8 V.

2.2 Cycle Life

- Stability: Mn-rich materials (y=0.5–0.7) retain >80% capacity after 100 cycles. Fe-rich materials (y>0.7) suffer from poor stability due to Jahn-Teller distortion and phase transitions.

- Capacity Decay Mechanism: Primarily caused by structural distortion during Na⁺ extraction/insertion and Mn³⁺ disproportionation.

2.3 Coulombic Efficiency

- Initial Efficiency: 70–80%; stabilizes above 95% after 5–10 cycles.

- Key Factors: Residual alkali content, solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) formation, and side reactions reduce initial efficiency.

2.4 Energy Density

- Practical Energy Density: 120–150 Wh/kg, approaching lithium iron phosphate (LFP) levels.

- Enhancement Strategies: Doping (e.g., Al³⁺, Ti⁴⁺) or surface coatings (e.g., carbon layers) further improve energy density.

| Fe/Mn Ratio | Synthesis Method | Specific Capacity (mAh/g) | Cycle Stability | Voltage Platform (V) | Remarks |

| 0.5/0.5 | Solid-State | ~160 | Moderate | 2.5–3.5 | Low cost but uneven homogeneity |

| 0.5/0.5 | Sol-Gel | ~170 | High | 2.5–3.5 | Homogeneous but complex process |

| 0.38/0.40 | Coprecipitation | ~190 | High | 2.5–3.5 | Requires Cu doping to suppress phase transition |

| 0.33/0.67 | Solid-State | ~175 | Moderate | 2.5–3.5 | Needs Sb doping to enhance stability |

3. Synthesis Processes

3.1 Synthetic Routes

- Solid-State Method: Traditional approach using Fe₂O₃, MnO₂, and Na₂CO₃ via ball milling and high-temperature sintering.

- Sol-Gel Method: Produces uniform nanocrystals but at higher costs.

- Coprecipitation Method: Suitable for industrial production, enabling precursor control via pH and precipitation agent concentration.

3.2 Sintering Parameters

- Temperature: Typically 900–1000°C; excessive temperatures cause Na loss and lattice distortion.

- Time: 6–12 hours; insufficient time risks incomplete reactions, while prolonged heating increases energy consumption.

3.3 Post-Treatment

- Washing: Removes residual alkali (Na₂CO₃) to lower the pH to 7–8.

- Drying: Spray or vacuum drying controls moisture content below 0.1%.

4. Challenges and Solutions

4.1 Phase Transition

- P2→O2 Phase Transition: Occurs during deep Na⁺ extraction, leading to capacity fade and voltage hysteresis.

- Mitigation: Al³⁺/Ti⁴⁺ doping or surface coatings inhibit phase transitions.

4.2 Air Stability

- Moisture Sensitivity: P2 structure degrades in air, compromising performance.

- Mitigation: Surface coatings (Al₂O₃/carbon layers) or inert gas protection.

4.3 Cost and Scalability

- Raw Material Costs: Mn/Fe are inexpensive, but purification processes may increase expenses.

- Industrialization: Requires optimized equipment (e.g., continuous sintering furnaces) and process parameters (e.g., atmosphere control).

5. Future Directions

P2-Naₓ(FeᵧMn₁⁻ʸ)O₂ holds significant advantages in cost, energy density, and safety. Future research should focus on:

- Element doping/coating to optimize cycle stability and rate capability.

- Interface engineering to suppress side reactions and improve initial efficiency.

- Industrial-scale production of low-cost, high-consistency materials to advance commercialization.

Conclusion

By tuning Fe/Mn ratios and optimizing synthesis processes, P2-Naₓ(FeᵧMn₁⁻ʸ)O₂ has emerged as a leading cathode material for sodium-ion batteries. Despite challenges like phase transitions and air sensitivity, material design and process improvements promise enhanced performance, offering a sustainable solution for energy storage applications.

Tags: Sodium ion batteries (SIBs), positive electrode materials, P2 Na ₓ (FeyMn ₁₋ y) O ₂, iron manganese based sodium ion positive electrode materials